The precious and versatile vegetable tissue known as cork is the outer bark of the cork oak tree (Quercus suber or as the Portuguese call it sobreiro). Cork (cortiça) is most easily stripped off the tree in late spring and summer when the cells are turgid and fragile and tear without being damaged. The tree quickly forms new layers of cork and restores its protective barrier. No tree is cut down. This simple fact makes cork harvesting exceptionally sustainable, leading to a unique balance between people and nature.

Cork has a structure that you can compare with that from a honeycomb. Every cm2 consists of approximately 40 million cells. These cells, as well as the spaces in between, are filled with a kind of gas resembling air, but without CO2. Thus the cork cells work as small sound and heat insulators and absorb pressure and shocks. This is what makes cork so remarkable. Up till today there has not been found any other material which combines the same characteristics as cork does.

Although the ancient Greeks and Romans knew about the value of cork bark, it only began to be harvested commercially in Portugal about three hundred years ago. It is still done by teams of men using hand axes and no viable mechanical method has yet been invented to do the job as effectively. It’s a highly skilled business where each generation has tutored the next in a continuous process from the time of the ancient Greeks.

The agricultural workers who harvest cork are among the highest paid agricultural field workers in the world, earning between 80 Euros to 120 Euros per day. The workers are provided with medical health care insurance and worker’s compensation insurance that provides wage replacement and medical benefits for the rare few who might get injured in the course of employment. The workers are sensibly paid not on the amount of weight they rush through to harvest, but instead are paid based on a fixed daily wage, in order to assure that they perform their harvesting work with due regard for the health of the trees.

The cork strippers (tiradors) work in pairs, one man clambering up the tree while the other stays on the ground. In unison they chop delicately into the dead bark, gauging its thickness by the sound resonating from the steel ax, and carve out door-sized rectangular slabs. The spongy cork peels like an orange, with a crackling, tearing sound, baring the tree's bright yellow, living layer of bark. This paler color will redden in a day or two; the inner bark will seal itself and take on an opaque, stuccoed look. As the years pass the bark will thicken and darken once again, to reddish mahogany, to chestnut, and back to silvery-charcoal grey.

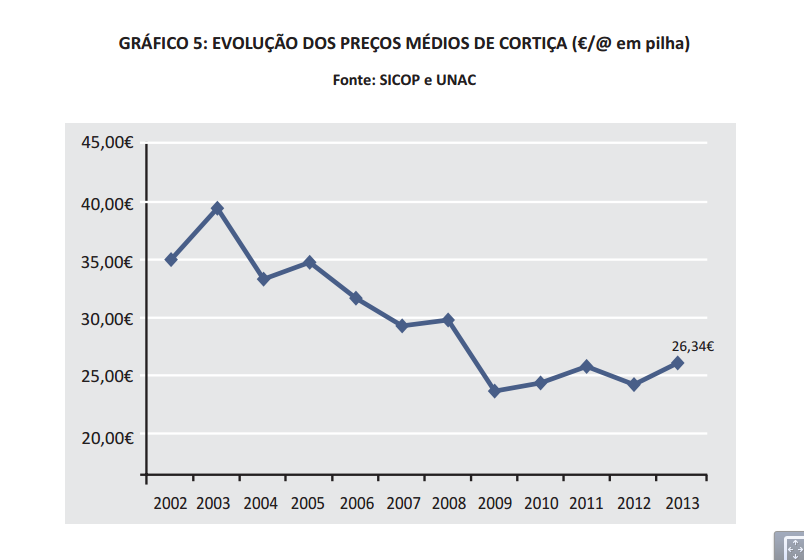

The unprocessed cork is measured in arroba (an equivalent of 15 kg). The sign for the arroba is @ Since 2003 the price of cork fell dramatically, from €44,80 per arroba piled cork to €26,34 in 2013. The extraction cost are around €4 per @

The bark of the cork oak is stripped away every nine to ten years and it takes at least 25 years for a new tree to become profitable for the first time.

The first stripping produces cork (virgin cork - "desbóia") that is too hard to be easily

handled because it has an irregular structure. It is used in products like flooring and insulation. 9 to 12

years later a second harvest produces better material, but still not

good enough for cork bottle-stoppers.

Only the third and subsequent

harvests produce cork with an even structure good enough to be used for

wine closures. The Portguese call this cork "amadia". The tree will provide a harvest for some 200 years.

Cork’s natural properties make it eminently suitable for its principle

use worldwide: as a bottle-stopper. It is very light, yet impermeable

to liquids and gases, elastic and compressible, an excellent insulator,

fireproof, and resistant to abrasion. Above all, it is completely

natural, renewable, and recyclable.

Montado - the unique cork oak landscapes of Portugal

In Portugal, where cork processing is a highly developed industry, cork oak landscapes are often dominated by a unique pastoral system shaped by humans, know as montado. The montado gives rise to a unique system of mixed farming, neither agriculture, forestry nor pastoralism, but an integrated mix of all three, designed and deveoped over millennia to secure the greatest abundance from often harsh and inhospitable conditions.

The indigenous oaks thrive, their primary growth period coinciding with the rainy season in spring. In turn, their acorns provide animal feed, and their large canopy shades the animals from the searing summer heat. A thick leaf litter creates humus, replenishing the soil and protecting it against wind and sun, thus preserving precious groundwater. The more open areas are used for grazing sheep, goats and cattle as well as the cultivation of crops.

The ancient Greeks so revered cork oak trees as symbols of liberty and honour, according to Pliny the Elder, that only priests were allowed to cut them down. Wine amphorae sealed with cork were found at Pompeii, and the first environmental laws protecting cork oak forests were passed in Portugal in the early 13th century. But the systematic exploitation of the great cork forests that can still be found on the Iberian peninsula dates only from 18th century, when the production of cork bottle-stoppers became the main objective.

Cork oak landscapes are one of the best examples of balanced conservation and development anywhere in the world. They also play a key role in ecological processes such as water retention, soil conservation, and carbon storage. Plant diversity can reach 135 species every square metre; many have aromatic, culinary, or medicinal value. The fertile undergrowth is thick with heathers, leguminous plants, rock roses, and herbs. Cork oak forests also host a rich diversity of fauna, including spiders, spadefoot toads, geckos, skinks, vipers, mongoose, wild cats, roe deer, boars, Barbary deer, and genets. The trees help conserve soil by protecting against wind erosion and increasing the rate at which rainwater is absorbed. Water erosion is also less in areas below upland forests that intercept rainfall, while reservoirs linked to irrigation and hydroelectric installations are protected from eroded soil.

Cork oak landscapes store carbon, reducing greenhouse gases in the

atmosphere, especially in the early years of their life when they grow

fast. Cork oak trees store carbon in order to regenerate their bark,

and a harvested cork oak tree absorbs up to five times more than one

that isn’t.

A decline in

demand for cork would be calamitous for the region's arid areas as well

as spell disaster for rare wildlife. Local farmers will only continue

to practice the traditional system of cork farming as long as it is

economically viable. The cork oak forests make up an ecosystem of

unparalleled biological richness. The cork oak trees preserve the

region's thin soils and scarce groundwater. Without them, the area will

quickly become a desert and virtually uninhabitable for humans. It

would also spell the end for the Iberian Lynx, which lives in many of

Spain and Portugal's cork forests, and which has been declared the

world's most endangered big cat. `The cork oak forests of Portugal are

Europe's Amazon forests,' said Jorge Paiva, a botanist at Coimbra

University. 'They support the greatest bio-diversity anywhere in

Europe.'

It is because of the high value of cork bark that this ancient

landscape with its rural culture and its wildlife has been protected

until today. But it's future is by no means certain. If the metal screw

caps and plastic were to completely replace natural cork to stop our

wine bottles, then a drastic change could be on the way because land

owners would have to replace their oak woodlands with other more

conventional crops. If the forests maintain their economic value,

people care for them, reducing the risk of fire and desertification.

But if the demand for cork is not maintained there’s a risk the cork

oak landscapes of the western Mediterranean will, within a decade, face

increased poverty, more forest fires, loss of biodiversity, and faster

desertification. The habitats have been ranked among the most valuable

in Europe and are listed in the European Council Habitats Directive.

Standing dead oaks are not an uncommon sight in montados, thanks to an extraordinary law that was pushed through in the 1970s by Portuguese cork producers, after 500,000 acres of cork had been replaced with eucalyptus for the pulp industry.

The law states that without permission from the government, it’s illegal to cut down any cork oak in Portugal, dead or alive. A landowner caught clearing a montado pays a steep fine and is barred from using the land for 25 years. The law has helped preserve montados in lean times, but land managers call it too restrictive; they can’t cull sick trees quickly to prevent infections from spreading. And although the Portuguese love their cork oaks, most people believe the law would not survive if cork revenues dried up.

Some cork facts:

- A tree that is 80 years old can produce 40-60kgs of natural cork when harvested.

- The average cork oak tree produces one tonne of raw cork which equates to 65,000 stoppers.

- 340,000 tonnes of natural cork stoppers are produced each year, equating to the weight of approximately 44,000 elephants

- One particular tree in Portugal, known as the 'Whistler Tree' because of the many singing birds attracted to it, is said to be 212 years old. It is estimated that this tree already produced more than 1,000,000 natural cork stoppers.

- A natural cork is able to maintain its full sealing capacity for more than 100 years owing to its elasticity and the waxes and fatty acids in its composition.

- Portugal produces more than 50% of all the cork in the world.

- The number written on a peeled cork oak refers to the year it was stripped, e.g. "9" refers to "2009".

- The best quality cork comes from the south of Portugal (Algarve and south Alentejo).

- The year rings of the cork oak tree can be seen in the cork layer: 8 complete rings and on each side half a year ring (the stripping of the tree takes place in the middle of the growing process).

- Before anything can be made of the cork, the material has to dry for a couple of months, after which it is boiled to kill all insects and bacteria and to make the bark more flexible.

- cork oak trees store carbon in order to regenerate their bark and a harvested cork oak tree absorbs up to 5 times more than one that is not.

- The cork peeling season traditionally starts with the first new moon of the month of May.

During the last decennia there was a massive dieback of cork oaks. The trees first get weakened by drought or insect pests. This makes them more vulnerable to pathogens such as the fungus Diplodia corticola and P. Cinnamomi, which are the main contributors to cork oak decline and often sudden death of the cork oak trees. The symptoms are trunk bleeding, exit holes and loss of crown foliage.

Disease can be further spread by harsh cleaning of the area with heavy machinery.

Today Portuguese scientists work on sequencing cork oak genome, which could improve quality of cork, eradicate disease and help the cork oak resist climate change.

Also more uses for cork are being discovered all the time. Aerocork is building a prototype plane, using cork and carbon as a environmentalfriendly alternate to PVC and NASA uses cork in thermal protection coating on the space shuttle's external fuel tank.

You can view an interesting documentary called "forest in a bottle" from EcologicalCork.com on Vimeo.com/3357193

There is a Cork Route starting in São Brás de Alportel, where you can take a journey to the world of cork. Here you can see, feel and experience cork production from the oak tree all the way to the factory. For more information: www.rotadacortica.pt